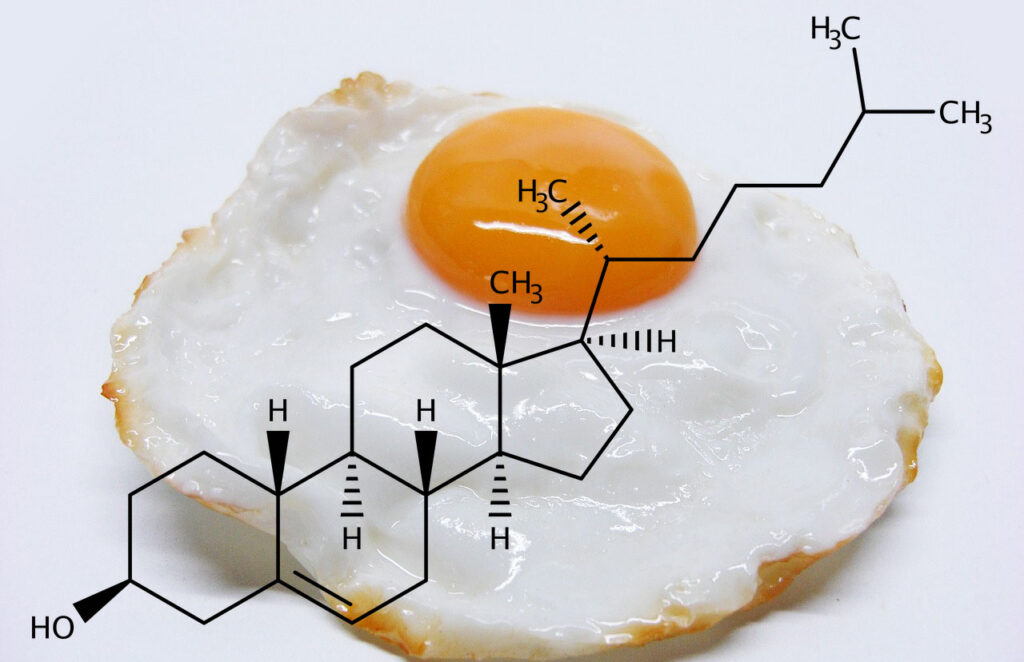

What is cholesterol?

Although the terms “fat” and “lipid” are used as synonyms, fats are a subgroup of lipids specifically referring to triglycerides. Other groups include monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, fat-soluble vitamins (D, E, K, A), and sterols, with the one that interests us the most being cholesterol.

Why is cholesterol important?

The cell membrane of mammals is composed of about 30% cholesterol. It is vital for maintaining its fluidity, structural integrity, and permeability. Cholesterol also plays a role in cell signaling and is a precursor of steroid hormones and bile acids.

How do we get cholesterol?

Every cell in humans and almost all animals (exceptions exist) can synthesize cholesterol (statins inhibit this process), but this process uses up decent amounts of energy. Consequently, to lower the energy demands of this process, we employ intestinal cholesterol absorption to utilize the 300-500mg of dietary cholesterol (from a Western diet) and 800-1200mg of our own bile cholesterol that passes through our gut every day.

Do we absorb all the cholesterol that ends up in our gut?

The short answer is no.

Basically, all the cholesterol we eat comes from animal sources, predominantly in esterified form. The main transporter on the enterocytes (cells of the gut wall) responsible for absorbing all sterols (zoosterols from animals, cholesterol being one of them, and phytosterolons from plants) into the cell is the Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 transporter (NPC1L1). The drug ezetimibe blocks this transporter in an effort to lower blood cholesterol.

The NPC1L1 can transport only unesterified cholesterol, even though pancreatic lipases manage to de-esterify ingested cholesterol (not finding a concrete number, sources stating from 10% to 100%), and bile cholesterol being completely unesterified. The average absorption of total cholesterol in our gut is still only about 50%, making the majority of the uptake our own bile-derived cholesterol.

Quick math: Let’s take the higher numbers, 500mg from food and 1200mg from bile, giving us 1800mg total. If 50% is absorbed (about 900mg), that’s some 300mg less than what is secreted in the form of bile, meaning we are losing more than we are taking in. This is okay because we are synthesizing a substantial part of our cholesterol needs.

Another mechanism that contributes to this partial absorption is that our own body can regulate how much cholesterol is absorbed from the lumen of our intestine based on our needs. Animal models and studies in humans suggest that the level of intracellular cholesterol can regulate the expression (the amount) of the NPC1L1 transporter on the enterocytes and also promote the excretion of cholesterol out of the enterocytes back into the gut lumen by the ATP-binding cassette transporters G5 and G8. In short, high intracellular cholesterol can reduce the number of transporters that absorb cholesterol from our gut and promote the excretion of already absorbed cholesterol in our gut wall back into the lumen to be pooped out, with the opposite happening when intracellular cholesterol is low.

Why is cholesterol considered to be bad then?

High levels of circulating cholesterol in our blood are indeed associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. Assessing this risk is not as simple as just knowing the total blood cholesterol. We must consider age, degree of present atherosclerosis, the number and type of lipoprotein particles (especially ones containing Apolipoprotein B100 and a variant of LDL called Lipoprotein (a)), family history, metabolic disorders, and other risk factors, but conclusively lower is better!

Conclusion.

We are reaching a consensus (from numerous papers and even the American Heart Association acknowledging it) that dietary cholesterol has minimal to no impact on blood serum cholesterol, but it’s not all black and white. The problem arises when we consider other nutrients accompanying a standard Western cholesterol-rich diet and lifestyle in general.

Processed foods containing refined fats (trans fats probably being the worst), added sugars, commonly high in fructose; excess of simple carbohydrates, even from plant sources; sugary beverages; alcohol; arguably saturated fat; not enough fiber, and generally a surplus of calories can increase one’s risk of cardiovascular disease directly or indirectly through developing metabolic disorders, inflammation, higher blood pressure, liver problems, and others…

My advice is to start early. The more time we have, and the better our blood lipid profile is, we can be less aggressive in our approach in lowering blood cholesterol through diet, lifestyle changes, and even medication if needed.